Lesson 9: Ties and Dots

Overview: This video covers Ties, Dots, Double Dots and introduces the 6/4 and 7/4 Time Signatures!

Assignment: Joel Rothman's Teaching Rhythm, pages 42 - 50: Get The Book (paid link)

You can also get a metronome here: Get the Metronome (paid link)

The next elements of music I’d like to cover are Ties and Dots. Ties and Dots are ways for a composer to extend the duration of a beat, but they do that in two very different ways. I'll start with ties.

The Tie

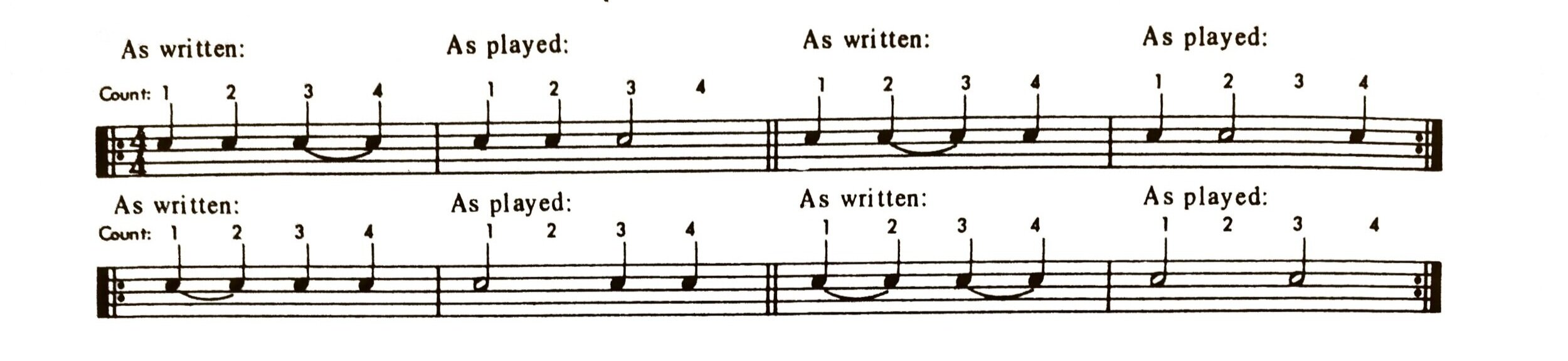

A tie is a curved line that connects two notes. Below are examples from Teaching Rhythm, page 42 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Ties Off Quarter Notes Source: Teaching Rhythm, Joel Rothman (c) 1967 Joel Rothman

The tie between notes tells the player to add the two note values together. You play the first note and you hold it throughout the duration of the second note.

You can actually have multiple ties in a row. You would just continue holding the note (or counting rests if you are playing drums).

It's important that you don't play the second (or third, or fourth, etc) note of the tied rhythms. You are just adding together their durations.

Ties are an element of music and not a type of rhythm because they can be added to any of the rhythms we've already learned. You could put ties on quarter notes, 8th notes, 16th notes, half notes or whole notes. All you need to do is add the rhythms together when they are tied.

The Dot

The next element of music is the Dot. Like the tie, the dot also extends the beat but it does it in a very specific way.

It extends the rhythm by half of the value of the note it's attached to. Here again, is the example from Teaching Rhythm.

Fig. 2 Dots After A Quarter Note Source: Teaching Rhythm, Joel Rothman (c) 1967 Joel Rothman

If you have a dotted half note, the dot extends the rhythm by 1 quarter note. Dotted quarter notes are extended by one 8th note. Dotted 8th notes are extended by one 16th note and so on.

One way to help you remember how much time to add to a dotted rhythm is to think of the table of time and how each duration is on its own level, like a pyramid (Fig. 3).

Start with the whole note at the top and start dividing the rhythms in half. Next, you'd get two half notes, then four quarter notes. Quarter notes split into eight 8ths and 8ths split into sixteen 16th notes.

Fig. 3 Table of Time - Pyramid Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

When you see a dotted half note like you do on page 45, you have to think of the rhythm in terms of its quarter note counterparts.

Remember, you extend the rhythm by half of its original value. So a half note is equal to two quarter notes. Half of that is one quarter note.

In other words, you have two quarter notes for the original half note and then the dot means to add one more quarter. So, the dotted half note is worth three quarter notes (Fig 4).

Fig. 4 The Dotted Half Note Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

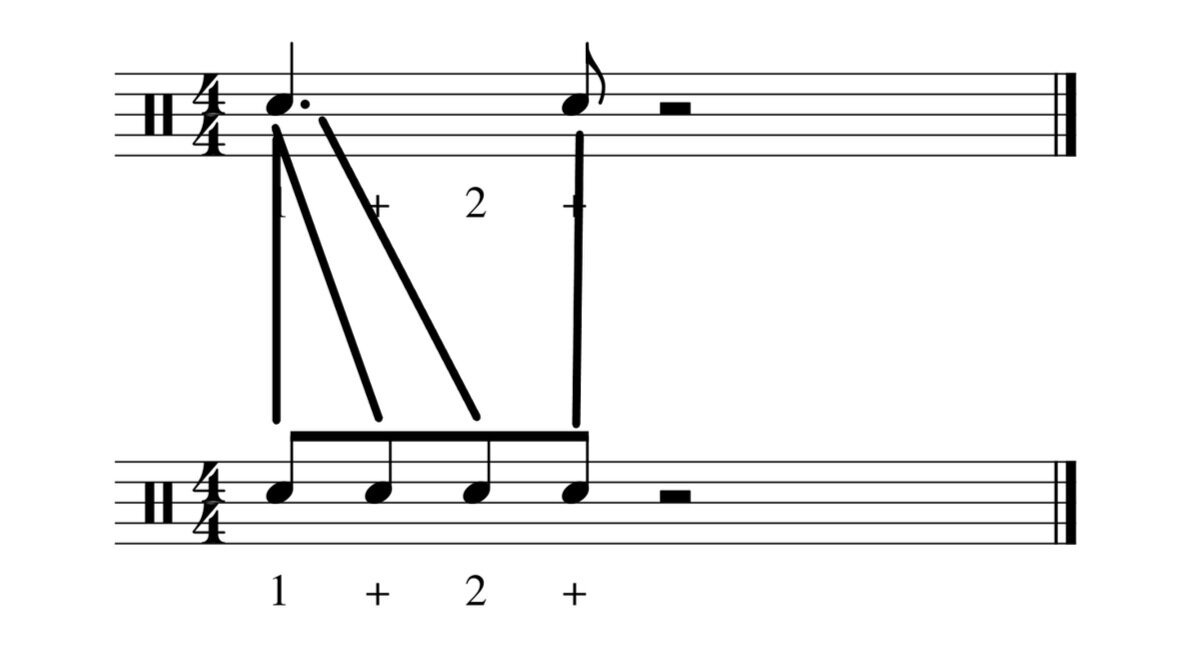

When you encounter a dotted quarter note, you do the same thing (Fig. 5). Think of the quarter note in terms of 8th notes. The quarter note takes up the same duration as two 8th notes. The dot extends that by one more 8th note. The dotted quarter note is worth three 8th notes.

Fig. 5 The Dotted Quarter Note Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

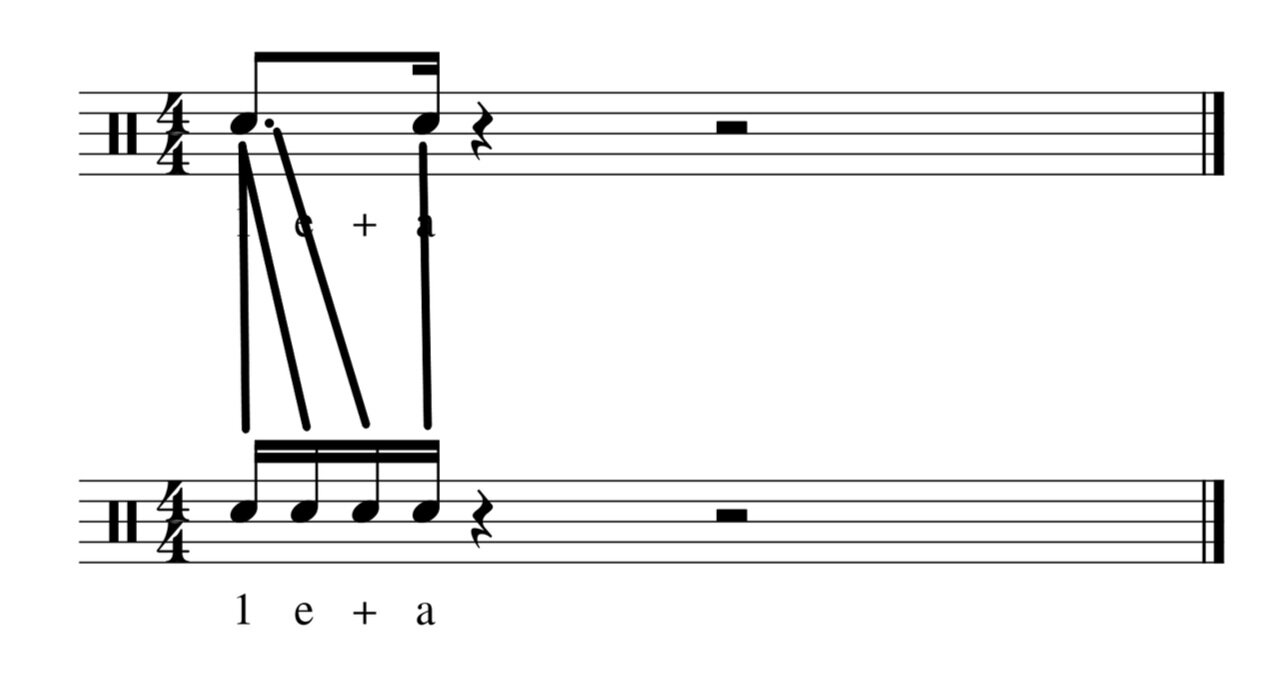

Think of Dotted 8th Notes in terms of 16th notes. One 8th note is worth two 16th notes, and the dot extends it to a third 16th note (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 The Dotted 8th Note Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

Just like the tie, the dot can be applied to any rhythm. A dotted whole note is worth three half notes, or six quarter note beats, for example. You can also mix dots and ties like the example excerpt here in 4/4 time (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Excerpt from Dots and Ties Mixed Source: Teaching Rhythm, Joel Rothman (c) 1967 Joel Rothman

The Double Dot

From time to time, you might also run into a rhythm with two dots. That’s called a Double Dot. In Joel Rothman's words, “two dots placed after a note increases its duration by three-fourths of its value.”

Let's go back to the pyramid (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Table of Time - Pyramid Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

When you have a double-dotted half note, like you do on page 49, what you do is skip the level of quarter notes and go right into 8th notes.

The half note is worth four 8th notes. Then you extend that by another three fourths. You extend it by an additional three 8th notes. So a double-dotted half note is worth seven 8th notes.

I like to think of it another way. I like to think of it as adding two separate dotted rhythms. Check out the example below (Fig. 9).

The first dot, like in the examples above, extends the half note to a third quarter note. But instead of being just a normal quarter note, it’s a dotted quarter note.

Then I think of that dotted quarter note in terms of 8ths. So instead of being worth just one quarter note, that rhythm is actually worth three 8th notes.

The total rhythm is then worth a half note plus a dotted quarter note. That’s two quarter notes plus three 8th notes added together, or seven 8th notes.

Fig. 9 The Double Dotted Half Note Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

A double dot on a quarter note means we’re going to be counting 16ths. Again, the first dot means you think in terms of 8th notes. A dotted quarter note is three 8th notes, but then you put the second dot on the last 8th note and it becomes worth three 16th notes. So your complete rhythm is worth two 8th notes plus three 16ths, or seven 16ths total (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10 The Double Dotted Quarter Note Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

Do The Math

These are the ways dots and ties extend the rhythm mathematically, but once you understand the concept and get used to playing these rhythms, you can start simplifying them in your mind.

It's been a while since I've seen double-dotted rhythms. They don't seem to be common in drum set music, but I don't exactly need to figure out how they work every time I see them either.

One of the things that I do when I have a difficult rhythm to read is what I call "doing the math of the measure".

On page 50, the first measure of the summary, which is in 5/4, contains a double-dotted half note (Fig. 11). Now let's pretend that it's the first time I've seen a double-dotted half note in a long time. To "do the math of the measure", I start with what I know.

Fig. 11 Double dotted half note from page 50 Summary Source: Teaching Rhythm, Joel Rothman (c) 1967 Joel Rothman

I know that I have five quarter notes in that measure because of the time signature, so I try to find all five quarter notes by adding up all the rhythms I understand.

The first rhythm I understand for sure is that the double-dotted half note starts on beat 1. That's because there are no other rhythms before it. So that's beat 1.

The next rhythm I see is this 8th note floating out in the middle of nowhere. That's the difficult rhythm because I don't know how long to hold the half note. I skip it for now and look at the next rhythm.

I see a quarter note. Since it's the last rhythm in the measure and it's a whole beat, I know that it's beat 5. It can't be anything else because it needs to take up a whole quarter note's worth of time.

So far I have beat 1 and 5 and now back to the problem child - that 8th note. Well, the quarter note on beat 5 gave me a huge clue.

Since I have to give that 8th note its full duration, it can only be on the "+" of beat 4. Any earlier than that and I would need other rhythms between it and beat 5. Any later, and it would overlap beat 5, which can't be done.

Now I know how long to hold that double-dotted half note even if I don't understand how it works.

Higher up on that page you'll see many dotted 8ths with 16ths (Fig. 12). That's actually just a very common rhythm in itself and will quickly become a part of your musical vocabulary.

Fig. 12 Dotted 8th plus 16th Note Rhythm Source: Teaching Rhythm, Joel Rothman (c) 1967 Joel Rothman

In the same way that you might piece together letters to make words, this rhythm is like a word. It's a very specific rhythm that someday you won't have to figure out every time you see it.

In The Practice Materials

If you are working along using Teaching Rhythm, you are introduced to two new time signatures 6/4 and 7/4.

I've talked a lot about time signature throughout the series, so I believe you should be able to get the hang of these two times. Just remember, the top number tells you how many beats there are in a measure and the bottom number tells you the type of note that gets the beat (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 The 6/4 and 7/4 Time Signatures Source: www.ChristianJohnsonDrums.com

In those exercises keep counting out loud and make sure to account for the full duration of notes and you should have no problem.

In Closing

So that’s it for this lesson. Thanks again for checking out the Rhythm and Reading Series. I hope you’re getting a lot out of it. I know I am (I totally forgot that the double dot even existed!)

We’re at a great crossroads here because, for now, I’ve ended my discussion of Duple Rhythms. Duple rhythms are rhythms that are created by subdividing into twos (1 x whole note = 2 x half notes = 4 x quarter notes = 8 x 8ths = 16 x 16ths, etc).

Next up I’ll be starting the series on Triplet Rhythms, which are rhythms that are created when you subdivide into threes! It’s the beginning of getting into more complex subdivisions.

I’ll also be branching off into a mini-series on Syncopation, which is a musical expression of rhythm that is notated in a specific way. It’s extremely common in modern pop and jazz music, and it’s everywhere in written drum music.

That’s all for now! You can get notified when I post new lessons by subscribing to my newsletter here or by subscribing to my YouTube channel.

See you next time!